- Home

- Helen C. Escott

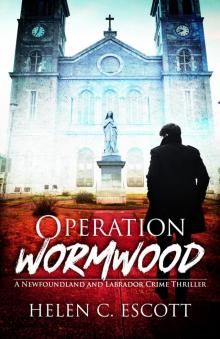

Operation Wormwood

Operation Wormwood Read online

Praise for

Operation Wormwood

“At the heart of this gut-wrenching, savagely realistic novel is a deep theological struggle: why does evil against the most vulnerable go unpunished by a loving, all-powerful God? Escott combines first-hand police experience, superb storytelling, and deep faith in this Dan Brown–style epic.”

Rev. Robert Cooke, Rector of the Parish of St. Mark the Evangelist and Adjunct Professor, Queen’s College Faculty of Theology

“Brilliant! Absolutely brilliant! With skilled, detective-like precision, Escott kept me at the edge of my seat throughout this well-told story of hurt and faith. Filled with a ton of well-researched facts and figures regarding Newfoundland and Labrador’s history, criminal investigative processes, and relevant political complications, this novel fills the reader’s need for action, suspense, and emotion. This book will make every Newfoundlander and Labradorian reflect on their complicated history and fully intrigue those who come from away. Operation Wormwood is wicked . . . simply wicked . . . in every definition of the word.”

E. B. Merrill, S/SGT. (Rtd.)

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Flanker Press Limited

St. John’s

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Escott, Helen C., 1963-, author

Operation Wormwood : a Newfoundland and Labrador

crime thriller / Helen C. Escott.

Issued also in electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77117-707-8 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77117-708-5

(EPUB).--ISBN 978-1-77117-709-2 (Kindle).--ISBN 978-1-77117-710-8

(PDF)

I. Title.

PS8609.S36 O64 2018 C813’.6 C2018-903512-9 C2018-903513-——————————————————————————————————————————————------——

© 2018 by Helen C. Escott

All Rights Reserved. No part of the work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical—without the written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed to Access Copyright, The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 800, Toronto, ON M5E 1E5. This applies to classroom use as well.

Printed in Canada

Cover design by Graham Blair

Flanker Press Ltd.

PO Box 2522, Station C

St. John’s, NL

Canada

Telephone: (709) 739-4477 Fax: (709) 739-4420 Toll-free: 1-866-739-4420

www.flankerpress.com

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Tourism, Culture, Industry and Innovation for our publishing activities. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $157 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country. Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. L’an dernier, le Conseil a investi 157 millions de dollars pour mettre de l’art dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

Dedication

I would never have written this book without the love and support of my husband, Robert—my hero and the real Sgt. Nicholas Myra. Thank you for believing in me long before I believed in myself. I love you forever and always.

It took ten years to write this book, and I always tell our children—Sabrina, Daniel, and Colin: Don’t give up on your dreams. My love for our children, and all children, was the reason I wrote this book. You three amazing kids have inspired me to keep going. Thanks for letting me be your mom.

I could not have worked through the issues in this book without the long walks and deep discussions I had with my best friend and faithful companion, Minnie. I saved you . . . then you saved me

It may only be a matter of time before God unleashes a plague upon the earth. — Sister Mary Pius

1

A thick fog hugged the streets of St. John’s, the oldest city in North America. The seaport had been surrounded by a bank of fog for three days. The cold, damp air crept into a person’s bones, causing a chill that not even a hot cup of tea could thaw. This type of spring weather could last for weeks, causing even the hardiest of Newfoundlanders to curse the damp cold and wonder why they didn’t move down south to a warmer climate. It wasn’t unusual for a person to develop anything from a common cold to pneumonia this time of year.

The emergency department at the Health Sciences Centre was alive with activity. Charles Horan struggled to carry Patrick Keating through the front doors of the hospital. The elderly Keating was barely able to stand and continuously passed in and out of consciousness. Horan wanted to call an ambulance, but Keating did not want the attention the lights and sirens would bring. The two men could have easily been mistaken for father and son.

The waiting room was standing room only. The thirty-year-old hospital had hardly kept up with the growing population of the province. The once state-of-the-art emergency department was in dire need of simple things like an updated seating area, a lick of paint, and more space. The sniffles and groans of sick people filled the area. The sign on the wall said estimated wait time: 4 hours. There were three wickets at the front of the room, each with clerks taking basic medical information from patients and determining their level of priority.

Keating’s right arm was draped across Horan’s shoulders. Horan held the elderly man tight around the waist to keep him from falling as he carefully helped him sit in front of a wicket. Keating’s body melted into the chair. The perspiration on his brow was visible, and his mouth sagged as if he was having a stroke. Horan quickly explained that Keating had been sick on and off for over a year. He had a flu that he could not get rid of. He told the nurse he begged the elderly man to go to the doctor, but Keating refused. His symptoms became worse over the past few months. He had an unquenchable thirst but found water bitter and turned his stomach. The thirst was followed by unstoppable nosebleeds. He had lost a considerable amount of weight but attributed this to stress and being overworked. He also had torturous pain throughout his body.

The nurse noted the symptoms and placed a hospital bracelet around Keating’s wrist. She prioritized him as urgent but not life-threatening. She brought out a wheelchair and, with Horan’s help, lifted Keating onto the padded seat. By this time, Keating was starting to come to and began talking nonsensically. He was unaware of his surroundings, and his speech slurred as he grabbed Horan by the collar and pulled him closer, whispering, “Don’t tell them who I am. I don’t want the media to get wind of this. I don’t want any rumours or panic.” Keating was winded and couldn’t focus his eyes.

“No, Patrick, don’t worry about things like that now. You’ll see a doctor soon, and you’ll be fine.”

Keating’s head fell forward, and he passed out again.

Agatha Catania, the emergency department nursing supervisor, didn’t care who he was. She was more interested in getting him into triage and assessed. With expert precision from years of crisis medical experience, she took Keating’s vital signs. His temperature was 101, his pulse was racing, his respiratory rate was laboured, and his blood pressure was 180 over 95.

She wheeled him into an examination room, and two more nurses assisted her, lifting him onto a bed. “We have to get him into a gown to be examined,” she said, and started to unbutton his shirt.

“N

o, I’ll do it.” Horan pushed her hands away from Keating’s chest. She shoved his hands back.

“I am a nurse, sir.”

Horan decided to divulge their secret. “He’s the Roman Catholic archbishop for the province, and I’m his assistant. We’re both priests. Please, let me do it.”

Agatha felt like he was expecting her to bow her head and genuflect at the mention of his title. She was the first person in her Conception Bay family to get a university degree. Her father, a weathered fisherman, broke his back to ensure his only daughter received a good education. He never wanted her to work on the water. Her family had Italian and English roots, but centuries of blending their accent with the local Irish dialect, spoken throughout this island in the cold North Atlantic, left them with a distinctly townie or bayman accent. She was a bayman and a proud Protestant raised in the Church of England but often mistaken for Irish Catholic due to her thick bayman pronunciation of certain words. Four years of university and ten years of working at the biggest hospital in the province could not take the bay out of the girl. Father Horan’s assumption that she was a good Catholic girl was more than justified by her words and actions.

Putting this old man into a johnny coat was one less thing she had to do during this busy shift. She moved back to allow Horan to unbutton the shirt. “I’m sorry. Go ahead. The doctor will be in shortly.” She walked out of the room, allowing the two men their privacy. By the time Dr. Luke Gillespie entered the examination room, Horan had the archbishop in his hospital gown and a blanket pulled up to his chest. He was mopping his supervisor’s brow with a cold face cloth.

“Your friend has a nasty flu, from the looks of this,” the doctor surmised while reading the vitals from a clipboard.

“For some time now,” Horan informed him.

“Let’s have a look.” Gillespie took his stethoscope from around his neck and began to listen to Keating’s heart and lungs. “How long has he been sick?” he asked as he took the stethoscope out of his ears.

“He’s had the flu on and off for a little over a year. He just can’t shake it,” Horan said. “It started getting worse a couple of months ago. He was tired all the time, and he has lost a considerable amount of weight, maybe twenty to twenty-five pounds, in a short period. He has fevers on and off, and diarrhea.”

Gillespie folded his arms and pondered his patient’s predicament. “How old is he?”

“He’ll be sixty in a month. One more thing,” Horan added. “He has this incredible thirst for water, but every time he drinks it, he throws it up, saying it’s bitter and vile.” Horan’s face showed concern and fear. “He also has uncontrollable nosebleeds. He can bleed for hours. I’ve never seen anything like it, and he complains of constantly being in pain. Sometimes the pain is so bad he cries, which is unlike him.”

The doctor could sense his attachment to this man.

Gillespie tilted the archbishop’s head back until his mouth opened and placed a tongue depressor inside. He shone a small penlight into his patient’s mouth. He was alarmed to see white spots and a thick coating on his tongue. The doctor threw the tongue depressor in the garbage and felt Keating’s lymph nodes in his neck and armpits. They were enlarged.

The archbishop began to come to and broke into a heavy cough. His throat was dry. He could not catch his breath, and his head fell forward. Horan put his arm under the archbishop’s shoulders and lifted him to open his airways. Without notice, he broke into a harder cough that came from the pit of his belly. Suddenly, blood spewed from his nose, splattering his chest. He coughed again, and the blood flew through the air. Gillespie instinctively jumped back, but the projectile blood splatter reached him, dotting the top of his scrubs. Keating slid back into a trance. The front of his hospital gown was soaked in his blood. Horan propped up the pillows as the doctor laid him back down.

“I keep him elevated when he is like this so he doesn’t choke on his own blood.” Horan stared at the doctor as if hoping for an answer.

Nurse Catania, followed by two other nurses, ran into the room, ready to take direction. “I want everyone who comes in here to be wearing latex gloves, masks, and gowns,” ordered Dr. Gillespie. “He is quarantined as of right now.” The three nurses left and headed toward the supply cabinet to get suited up.

Father Horan was shaking. “Does he really need to be quarantined?”

“It’s standard procedure when staff is exposed to blood. You’ll have to go to the waiting area.” The doctor pointed toward the door.

“Is he going to be all right? I have to notify some people of his situation.” Horan took note of the concern on Gillespie’s face.

“Call whoever you need. We’re going to run some tests now.”

Dr. Gillespie felt a sense of panic come over him. He quickly scrubbed the blood off his hands and checked in the mirror to see if any had landed on his face. It was clean. “Thank God for that,” he whispered to himself.

Nurse Catania returned, covered in a mask and gown. “Are you all right? What is it?” The look on the doctor’s face stopped her in her tracks.

Gillespie hesitated. “I’m okay. I’m thinking of a few possible causes. I can’t be sure till I get the tests back.” He looked at his patient, who was unconscious in the bed. “I’ll write up a requisition for blood and urinalysis. Make sure no one else comes into this room, and keep yourself covered.”

“Do you think it’s another wave of something like SARS?” Agatha knew she’d have a mountain of paperwork if it was.

Several causes were running through his head. “I’m not sure, but I think it’s more serious than the flu.” Gillespie looked at the chart again “Who is he? His name and face are familiar.”

“Are you Catholic?” Agatha asked.

He looked at her like he didn’t understand what language she was speaking. “I was born Catholic, but I haven’t practised in a long time.”

“He is the Catholic archbishop for the province. The other gentleman is his assistant.”

“I haven’t been to church in a long time. He wouldn’t be familiar to me. Maybe to my mother,” he added as an afterthought. Gillespie shrugged. “I don’t care who he is. He’s a patient to me. Money and power are no good to anyone in a hospital bed.”

* * * * *

It took a few hours to get the X-rays back. Dr. Gillespie stood in the emergency room office examining the test results and looking at the archbishop’s results displayed upon the wall when Nurse Catania approached him.

“What does it show?” She stood next to him looking at the screen.

Gillespie shook his head. “I don’t know. I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

Nurse Catania picked up the paperwork from his desk and read the results. “He has an infection. That’s obvious.”

“My gut told me to test for AIDS or HIV,” he confessed.

Agatha looked at him with a smirk on her face. “Really?”

He looked away from the X-rays. “The white spots on his tongue and the swollen lymph nodes in his neck and armpits give me concern. I have to go with my gut.”

Agatha laid the paperwork down on the desk. “What about a disease similar to SARS?”

“No. Tests are clean for that, too. As a matter of fact, according to all these tests, he is as healthy as a horse. I thought for sure it was going to be tuberculosis, but his lungs are clear.” Luke was thinking out loud. “I’m at a loss. I’m really at a loss.”

“I just checked on him before coming in here. He’s still unconscious, and he hasn’t had another bleeding episode yet. So, what now?”

Gillespie was running symptoms and diseases through this mind like a computer searching for information. “He’s not fitting into any one disease. It seems like he has bits and pieces of several diseases.” A thought popped into his head. “Does his chart say anything about him be

ing a hemophiliac?”

“I don’t think so. I’ll check.” Catania left the room and returned a few minutes later with the archbishop’s chart. “No. Nothing about any type of bleeding disorder. Do you want me to test him?”

“Yes. Maybe we’ll find a clue there.”

Agatha returned to the main nursing station and retrieved the needle and rubber tourniquet to take blood from the archbishop. The nurse at the counter informed her that Father Charles Horan was in the waiting room and wanted to speak to someone.

She put her supplies in her uniform pocket and headed to the waiting area. Horan was pacing in the hallway with a cellphone to his ear, speaking to someone about the archbishop’s situation. He said goodbye when he saw Nurse Catania coming toward him.

“Any news?” He was anxious, and his hands were shaking as he tried to put the cellphone into the holster on his belt.

“Not yet. We’re running tests. Can you think of anything that may be causing this?”

Horan shook his head. “He was always healthy and active up until a little over a year ago. He caught the flu and couldn’t shake it. He would often complain of pain, saying he thought every nerve in his body was on fire.” He shoved his hands in his pants pocket and looked worriedly toward the ceiling.

Nurse Catania wasn’t sure if he was looking for answers or divine intervention. She noticed how young this priest was—he couldn’t be more than twenty-five. Yet the lines around his eyes made him look much older. He seemed too young to have the responsibility of caring for the head of the church in this province.

“I have seen similar symptoms in a few other priests, but not as severe as the archbishop’s,” Horan confessed.

“You told us when you came in that no one else around him had these symptoms,” the nurse reminded him.

“Not as severe as his. The rectory is old. It’s not unusual to hear people complaining about the cold and damp in the rooms. It’s easy to catch a flu there, but no one has been as violently ill as the archbishop.”

Operation Wormwood

Operation Wormwood